- Home

- Vera Brittain

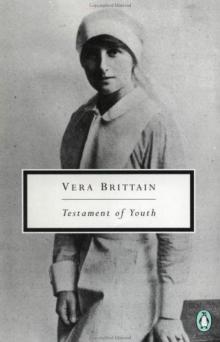

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Page 24

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Read online

Page 24

‘It is always so strange that when you are working you never think of all the inspiring thoughts that made you take up the work in the first instance. Before I was in hospital at all I thought that because I suffered myself I should feel it a grand thing to relieve the sufferings of other people. But now, when I am actually doing something which I know relieves someone’s pain, it is nothing but a matter of business. I may think lofty thoughts about the whole thing before or after but never at the time. At least, almost never. Sometimes some quite little thing makes me stop short all of a sudden and I feel a fierce desire to cry in the middle of whatever it is I am doing.’

As the wet, dreary autumn drifted on into grey winter, my letters to him became shorter and a little forlorn, though my constant awareness of his far greater discomforts made me write of mine as though they possessed a humour of which I was too seldom conscious. The week-ends seemed especially tiring, for on Saturdays and Sundays even the workmen’s trams ceased to function, and the homeward evening walk through the purlieus of Camberwell was apt to become more adventurous than usual.

‘I picture to myself,’ I told Roland, ‘Mother’s absolute horror if she could have seen me at 9.15 the other night dashing about and dodging the traffic in the slums of Camberwell Green, in the pitch dark of course, incidentally getting mixed up with remnants of a recruiting meeting, munition workers and individuals drifting in and out of public houses. It is quite thrilling to be an unprotected female and feel that no one in your immediate surroundings is particularly concerned with what happens to you so long as you don’t give them any bother.’

After twenty years of sheltered gentility I certainly did feel that whatever the disadvantages of my present occupation, I was at least seeing life. My parents also evidently felt that I was seeing it, and too much of it, for a letter still exists in which I replied with youthful superiority to an anxious endeavour that my father must have made to persuade me to abandon the rigours of Army hospitals and return to Buxton.

‘Thank you very much for your letter, the answer to which really did not require much thinking over,’ I began uncompromisingly, and continued with more determination than tact: ‘Nothing - beyond sheer necessity - would induce me to stop doing what I am doing now, and I should never respect myself again if I allowed a few slight physical hardships to make me give up what is the finest work any girl can do now. I honestly did not take it up because I thought you did not want me or could not afford to give me a comfortable home, but because I wanted to prove I could more or less keep myself by working, and partly because, not being a man and able to go to the front, I wanted to do the next best thing. I do not agree that my place is at home doing nothing or practically nothing, for I consider that the place now of anyone who is young and strong and capable is where the work that is needed is to be done. And really the work is not too hard - even if I were a little girl, which I no longer am, for I sometimes feel quite ninety nowadays.’

Fortunately most of my letters home were more human, not to say schoolgirlish, in content. Their insistent suggestions that my family should keep me supplied with sweets and biscuits, or should come up to London and take me out to tea, are reminders of the immense part played by meals in the meditations of ardent young patriots during the War.

3

Apart from all these novel experiences, my first month at Camberwell was distinguished by the one and only real quarrel that I ever had with Roland. It was purely an epistolary quarrel, but its bitterness was none the less for that, and the inevitable delay between posts prolonged and greatly added to its emotional repercussions.

On October 18th, Roland had sent a letter to Buxton excusing himself, none too gracefully, for the terseness of recent communications, and explaining how much absorbed he had become by the small intensities of life at the front. As soon as the letter was forwarded to Camberwell, I replied rather ruefully.

‘Don’t get too absorbed in your little world over there - even if it makes things easier . . . After all the War cannot last for ever, and when it is over we shall be glad to be what we were born again - if we can only live till then. Life - oh! life. Isn’t it strange how much we used to demand of the universe, and now we ask only for what we took as a matter of course before - just to be allowed to live, to go on being.’

By November 8th no answer had come from him - not even a comment on what seemed to me the tremendous event of my transfer from Buxton into a real military hospital. The War, I began to feel, was dividing us as I had so long feared that it would, making real values seem unreal, and causing the qualities which mattered most to appear unimportant. Was it, I wondered, because Roland had lost interest in me that this anguish of drifting apart had begun - or was the explanation to be found in that terrible barrier of knowledge by which War cut off the men who possessed it from the women who, in spite of the love that they gave and received, remained in ignorance?

It is one of the many things that I shall never know.

Lonely as I was, and rather bewildered, I found the cold dignity of reciprocal silence impossible to maintain. So I tried to explain that I, too, understood just a little the inevitable barrier - the almost physical barrier of horror and dreadful experience - which had grown up between us.

‘With you,’ I told him, ‘I can never be quite angry. For the more chill and depressed I feel myself in these dreary November days, the more sorry I feel for you beginning to face the acute misery of the winter after the long strain of these many months. When at six in the morning the rain is beating pitilessly against the windows and I have to go out into it to begin a day which promises nothing pleasant, I feel that after all I should not mind very much if only the thought of you right in it out there didn’t haunt me all day . . . I have only one wish in life now and that is for the ending of the War. I wonder how much really all you have seen and done has changed you. Personally, after seeing some of the dreadful things I have to see here, I feel I shall never be the same person again, and wonder if, when the War does end, I shall have forgotten how to laugh. The other day I did involuntarily laugh at something and it felt quite strange. Some of the things in our ward are so horrible that it seems as if no merciful dispensation of the Universe could allow them and one’s consciousness to exist at the same time. One day last week I came away from a really terrible amputation dressing I had been assisting at - it was the first after the operation - with my hands covered with blood and my mind full of a passionate fury at the wickedness of war, and I wished I had never been born.’

No sudden gift of second sight showed me the future months in which I should not only contemplate and hold, but dress unaided and without emotion, the quivering stump of a newly amputated limb - than which a more pitiable spectacle hardly exists on this side of death. Nor did Roland - who by this time had doubtless grown accustomed to seeing limbs amputated less scientifically but more expeditiously by methods quite other than those of modern surgery - give any indication of understanding either my revulsion or my anger. In fact he never answered this particular communication at all, for the next day I received from him the long-awaited letter, which provoked me to a more passionate expression of apprehensive wrath than anything that he had so far said or done.

‘I can scarcely realise that you are there,’ he wrote, after telling me with obvious pride that he had been made acting adjutant to his battalion, ‘there in a world of long wards and silent-footed nurses and bitter, clean smells and an appalling whiteness in everything. I wonder if your metamorphosis has been as complete as my own. I feel a barbarian, a wild man of the woods, stiff, narrowed, practical, an incipient martinet perhaps - not at all the kind of person who would be associated with prizes on Speech Day, or poetry, or dilettante classicism. I wonder what the dons of Merton would say to me now, or if I could ever waste my time on Demosthenes again. One should go to Oxford first and see the world afterwards; when one has looked from the mountain-top it is hard to stay contentedly in the valley . . .’

‘Do

I seem very much of a phantom in the void to you?’ another letter inquired a day or two later. ‘I must. You seem to me rather like a character in a book or someone whom one has dreamt of and never seen. I suppose there exists such a place as Lowestoft, and that there was once a person called Vera Brittain who came down there with me.’

After weeks of waiting for some sign of interested sympathy, this evidence of war’s dividing influence moved me to irrational fury against what I thought a too-easy capitulation to the spiritually destructive preoccupations of military service. I had not yet realised - as I was later to realise through my own mental surrender - that only a process of complete adaptation, blotting out tastes and talents and even memories, made life sufferable for someone face to face with war at its worst. I was not to discover for another year how completely the War possessed one’s personality the moment that one crossed the sea, making England and all the uninitiated marooned within its narrow shores seem remote and insignificant. So I decided with angry pride that - however tolerant Roland’s mother, who by his own confession had also gone letterless for longer than usual, might choose to be - I was not going to sit down meekly under contempt or neglect. The agony of love and fear with which the recollection of his constant danger always filled me quenched the first explosion of my wrath, but it was still a sore and unreasonable pen that wrote the reply to his letter.

‘Most estimable, practical, unexceptional adjutant, I suppose I ought to thank you for your letter, since apparently one has to be grateful nowadays for being allowed to know you are alive. But all the same, my first impulse was to tear that letter into small shreds, since it appeared to me very much like an epistolary expression of the Quiet Voice, only with indications of an even greater sense of personal infallibility than the Quiet Voice used to contain. My second impulse was to write an answer with a sting in it which would have touched even R. L. (modern style). But I can’t do that. One cannot be angry with people at the front - a fact which I sometimes think they take advantage of - and so when I read “We go back into the trenches tomorrow” I literally dare not write you the kind of letter you perhaps deserve, for thinking that the world might end for you on that discordant note.

‘No, my metamorphosis has not been as complete as yours - in fact I doubt if it has occurred at all. Perhaps it would be better if it had, for it must be very pleasant to be perfectly satisfied both with yourself and life in general. But I cannot . . . Certainly I am as practical and outwardly as narrow as even you could desire. But although in this life I render material services and get definite and usually immediate results which presumably ought therefore to be satisfying, I cannot yet feel as near to Light and Truth as I did when I was “wasting my time” on Plato and Homer. Perhaps one day when it is over I shall see that there was Light and Truth behind all, but just now, although I suppose I should be said to be “seeing the world”, I can’t help feeling that the despised classics taught me the finest parts of it better. And I shan’t complain about being in the valley if only I can call myself a student again some day, instead of a “nurse”. By the way, are you quite sure that you are on “the mountain-top”? You admit yourself that you are “stiff, narrowed, practical, an incipient martinet”, and these characteristics hardly seem to involve the summit of ambition of the real you. But the War kills other things besides physical life, and I sometimes feel that little by little the Individuality of You is being as surely buried as the bodies are of those who lie beneath the trenches of Flanders and France. But I won’t write more on this subject. In any case it is no use, and I shall probably cry if I do, which must never be done, for there is so much both personal and impersonal to cry for here that one might weep for ever and yet not shed enough tears to wash away the pitiableness of it all.’

To this unmerited outburst, though I received other letters from him, I did not get an answer for quite a long time. Just before I wrote it he was transferred to the Somerset Light Infantry for temporary duty, and could get his letters only by riding over some miles of water-logged country to the 7th Worcesters’ headquarters at Hebuterne, which was not, in winter, a tempting afternoon’s occupation. But when, at the end of November, the reply did come, it melted away my fear of his indifference into tears of relief, and made me, as I confessed to my diary, ‘nearly mad with longing for him, I wanted him so’.

‘Dearest, I do deserve it, every word of it and every sting of it,’ he wrote in a red-hot surge of impetuous remorse. ‘ “Most estimable, practicable, unexceptional adjutant.” . . . Oh, damn! I have been a perfect beast, a conceited, selfish, self-satisfied beast. Just because I can claim to live half my time in a trench (in very slight, temporary and much exaggerated discomfort) and might possibly get hit by something in the process, I have felt myself justified in forgetting everything and everybody except my own Infallible Majesty . . . And instead of calling it selfishness pure and simple I call it “a metamorphosis”, and expect, in consequence, consideration and letters which can go unanswered.’

He didn’t deserve, he concluded, to get my letters at all, but only to be ignored as completely as he had ignored me and his family. Apparently he had found my unhappy little tirade as soon as he arrived at Hebuterne that afternoon; it made him, he told me, so furious with himself that he left the rest of his correspondence lying on the table and rode straight back.

‘I don’t think I have ever been so angry or despised myself so much. I feel as if I hardly dare write to you at all. And to make it worse I have given up my chance of getting any leave before Christmas in order to be with this battalion a month instead of only a week. Oh, damn!’

For the time being, at any rate, these young, inflammatory emotions had burned down whatever barrier might have existed, and once more his letters became alive and warm with all the sympathy that I could desire for the unæsthetic bleakness of days and nights in hospital. But I, too, had by then something more to write about than the grey duties of Camberwell, for in the interval between my angry letter and his repentant response I had been down again - and for the last time - to Lowestoft.

4

One strenuous evening, after a month’s work at the 1st London General, I nearly fainted in the ward and had to be put to bed in a Sister’s cubicle at the hospital. I was intensely surprised and humiliated by this weakness, of which I had never before been guilty and was not to repeat. Probably the grim, suppurating wounds of the men in the huge ward were partly responsible, although, as I was to learn later in France, they were by no means the worst wounds that a man could receive without immediately qualifying for the mercy of death. Nevertheless, I had found them bad enough to make me pray nightly that Roland, for whom I had once regarded a wound as a desirable experience which might enable me to see him for weeks and perhaps months, might go through the War with body unscathed even though I never saw him at all.

‘From my inmost heart,’ I told him, ‘I have taken to cursing the War . . . and the jarringness of even healed mutilations, and the ghastly look of wounds which are never the same in different people and which one can therefore never get used to. When it is all over - if it ever is - one will have to get out of the habit of retrospect . . . Dearest, I don’t want you to get wounded now - not even a little. This War means such a waste of life even when people don’t die.’

I knew that I was to see the doctor next morning, and lay awake half the night in terror lest I should be found medically unfit to nurse, and returned ignominiously home like a garment vainly sent on approval. Perhaps, I thought, the quarrel with Roland and the endless waiting for an answer to my angry letter had lowered my resistance to septic infection. Perhaps even the gramophones, oppressive and persistent, had contributed to my humiliation.

‘In a surgical ward,’ I had told Roland a little earlier, ‘the nurses hardly occupy the silent-footed, gliding role which they always do in story-books and on the stage. For one thing, there is too much work to be done in a great hurry. For another, the mixture of gramophones and people shouting or g

roaning after an operation relieves you of the necessity of being quiet as to your footsteps, for it drowns everything else.’

They were blaring, blatant gramophones, and though the men found them consoling - perhaps because they subdued more sinister noises - they seemed to me to add a strident grotesqueness to the cold, dark evenings of hurry and pain. Many a man beyond the reach of harmony or discord must have breathed his last to the tune of ‘When Irish eyes are smilin”; many a diseased, feverish brain must have wondered when it returned to normality why it was ceaselessly haunted by the strains of ‘If you were the only girl in the world’. One Harry Lauder ditty, of which I cannot remember the beginning or the end, was invariably turned on just before the evening washings and temperatures; it had an insistent refrain which rang in my head all that autumn and always brought Roland vividly before me:

Don’t - forget - yer - sodjer - laddie

When - he’s - fightin’ - at - the Wa-ar!

The time draws near that I must leave ye,

But I knaw - that - ye’ll - be - TROO—

Soon after breakfast the doctor appeared - a young, sensitive man who died of cholera in the Persian Gulf a few months later. He tested my heart and pronounced me constitutionally fit, but said that I must have an immediate rest. Although my temperature was still slightly up, and no one knew whether I had anywhere accessible to go, I was ordered to leave the hospital at once on week-end sick-leave.

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925