- Home

- Vera Brittain

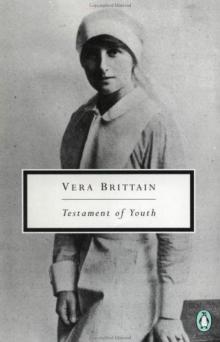

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Page 20

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Read online

Page 20

In the middle of August, to conclude three miserable weeks of disappointment, and parting, and anxiety, and depression following the news of the expensive operations at Suvla Bay, the first death that I had ever witnessed occurred at the hospital. Although surprised at my own equanimity, I had not yet acquired the self-protective callousness of later days, and I put into the writing of my diary that evening an emotion comparable to the feeling of shock and impotent pity that had seized Roland when he found the first dead man from his platoon at the bottom of the trench:

‘Nothing could have looked more dreadful than he did this morning, lying on his back worn just to skin and bone and a ghastly yellowish colour all over. He lay with his eyes half closed and turned up so that only the whites were showing, and kept plucking at the bed-clothes and pulling them down. It quite made me shudder to see his great bony hands at the end of his thin skeleton arms. He died from a most obscure complaint; they do not know exactly, I think, what it is. I pray that when I come to die it may not be like that. We ought to pray in our litany for deliverance from a lingering as well as from a sudden death. It is not death itself that presents such terrors to the mind but dissolution - and when that begins before death . . . It seems sad that he should die like this in the midst of strangers, with Sister beside him of all people, and no one really to care very much . . . To me it is strange that I take this death - sad as it makes me feel - so much as a matter of course when only a short time ago the idea of death made me shudder and filled me with horror and fear. From the time Nurse Olive related to me the one or two deaths she had been present at and I thought her callous to take it so much as a matter of course, to the time when I take it as a matter of course myself, I must have undergone a great revulsion of mind . . . And now that he is dead, reasonable as I try to be I cannot make myself feel that the individual, whatever it may have been, has really vanished into nothing and is not. I merely feel as if it had gone away into another place, and the worn-out shell that the men carried away was not Smith at all.’

10

‘Never, never,’ begins my diary for August 18th, ‘have I been in such agitation before. He has got leave; he is in England now. This morning as I was dusting bedsteads at the hospital Mother came with a wire from Mrs L. to say: “Roland comes home today!” ’

At midday a telegram sent off from Folkestone by Roland himself came to confirm the news. The afternoon interval of freedom was spent in the usual prolonged endeavour - inevitable owing to the distance between our homes - to get into touch by telegraph or telephone. Finally Roland wired asking if I would meet him next morning at St Pancras, and the Matron, to whose interested ears my mother had already confided the news of our unofficial relationship, gave me leave from the hospital for a long week-end.

No one, this time, suggested going with me to London; already the free-and-easy movements of girl war-workers had begun to modify convention. So I went up to town by the early train, to be at last alone with Roland for an uninterrupted day. Feverishly excited as I had been since the previous morning, I found it very difficult to realise that I was actually doing what I had dreamed of for months. To read was quite impossible, and I spent the entire four-hour journey in agitatedly wondering how much he would have altered.

During the few minutes that I had to wait at St Pancras for him to arrive from Liverpool Street, I shivered with cold in spite of the hot August noon. When at last I saw him come into the station and speak to a porter, his air of maturity and sophistication turned me stiff with alarm.

At that stage of the War it was fashionable for officers who had been at the front to look as disreputable and war-worn as possible in order to distinguish them from the brand-new subalterns of Kitchener’s Army. Not until later, when almost every young officer except eighteen-year-old cadets had been abroad at one time or another, was it comme il faut to model one’s self the more assiduously on a tailor’s dummy the longer one had been in the trenches. Modishly shabby, noticeably thinner and looking at least thirty, Roland on leave seemed Active Service personified.

In another moment we were standing face to face, tense with that anxiety to find one another unchanged which only lovers know at its worst. Just as we had parted we shook hands without any sign of emotion, except for his usual pallor in moments of excitement. For quite a minute we looked at each other without speaking, and then broke awkwardly into polite conversation.

‘What shall we do?’

‘Oh, I don’t know.’

‘Don’t you think we’d better go and have lunch somewhere?’

‘All right, but isn’t it a little early?’

‘Oh, never mind!’

So we went once again to the Florence, and, on the way there, looked out of opposite windows in the taxi. Even when we had sat down at our table, it was difficult to begin anything - including luncheon. We started to thaw only when I told him that, half waking one morning, I seemed to hear an inner voice saying quite audibly: ‘Why do you worry about him? You know he will be all right.’

This information stirred his customary conscious optimism into expression.

‘All along I have felt I shan’t be killed. In fact I may almost say I know it. I quite think I shall be wounded, but that is all.’

And when I recalled how much he had once wanted to go to the Dardanelles, where the casualties were so terrible, he rejoined with gay confidence: ‘Oh, I should have come through even there!’

‘Your hair’s just like a bristly doormat!’ I told him inconsequently, and he endeavoured, quite unsuccessfully, to smooth his close-cropped head with his strong fingers as he remarked that after all he hadn’t had such a bad time in France or ever been in specially dangerous trenches.

‘In fact,’ he concluded, ‘in many ways it’s quite a nice life!’ His one regret appeared to be that his regiment had not yet taken part in even a minor action.

A good deal of that afternoon was spent in discussing how much we should be able to see of each other during my precious week-end. After prolonged argument we agreed that, as my family were expecting me and I had no luggage, he should come back to Buxton with me for the night; I could then, I said, return with him to Lowestoft from Saturday till Monday.

In these maturer years I have often reflected with amazement upon the passionate selfishness of twenty-year-old love. During that brief respite from clamorous danger Roland must have needed, above all things, rest and freedom from noise, yet without compunction I involved him in a series of tedious, clattering journeys. He must have dreamed in crowded dug-outs of the peace and privacy of his bedroom at home, yet later, when I arrived at Lowestoft, I accepted with equanimity the fact that in occupying it I had turned him out to share a room with his brother. Not once did it occur to me - nor even, I believe, to him - that my company was dearly bought at the expense of his comfort.

Into the midst of our discussion of time-tables we sandwiched a visit to Camberwell, for, in spite of the previous day’s preoccupations, I had remembered to write for an appointment with the Matron of the 1st London General. A very small woman, grave and immensely dignified, the Matron seemed to me unexpectedly young for such an impressive position.

‘I stood,’ I recorded afterwards, ‘all through the interview, and know now just how a servant feels when she is being engaged.’

‘And what is your age, nurse?’ the Matron inquired, after hearing the necessary details of my Devonshire Hospital experience.

‘Twenty-three,’ I replied, promptly but mendaciously, giving the minimum age at which I could be accepted in an Army hospital under the War Office, as distinct from the smaller hospitals run by the Red Cross and the St John Ambulance Brigade. Since I still looked, in the provincial excessiveness of my best coat and skirt, an unsophisticated seventeen, she probably did not believe me, but being a woman of the world she accepted the bold statement at its face value, and promised to apply for me in October as soon as their new huts were ready.

When telegrams had been sent to Buxton

and Lowestoft, and the time for returning to St Pancras arrived with surprising suddenness, the thought of parental reactions on both sides became a little subduing. In those days, as we knew well enough, parents regarded it as a bounden duty to speak their minds at every tentative stage of a developing love-affair; they had none of that slightly intimidated respect which modern fathers and mothers feel for the private preoccupations of their self-possessed and casual children.

During dinner in the train we discussed the still critical attitude of the wartime world towards the relations of young men and women, and railed against society for its rude habit of waking one out of one’s dreams. We foresaw a series of ‘leaves’ in which our meetings would be impeded by suspicion, and our love tormented by ceaseless expectant inquiries. After Derby, for the first time, we had the carriage to ourselves. Almost immediately he came quite close to me and asked, with a queer little smile, half cynical, half shy: ‘Would it make things better if we were properly engaged?’

For the remainder of the journey to Buxton we argued on this topic almost to the point of quarrelling. I even told him, I remember, that he had spoilt everything by being so definite, for we both felt thoroughly bad-tempered over the situation into which an elderly, censorious society appeared to have manœuvred us. We did not want our relationship, with its thrilling, indefinite glamour, shaped and moulded into an acknowledged category; we disliked the possibility of its being labelled with a description regarded as ‘correct’ by the social editor of The Times. Most of all, perhaps, we hated the thought of its shy, tender, absorbing progress being ‘up’ for discussion by relatives and acquaintances.

‘A mere boy-and-girl affair between a callow subaltern and a college student! This dreadful War, you know - it makes young people lose their heads so, doesn’t it?’

I could hear some of my critical aunts and uncles revelling in the words; for this is the way in which disapproving middle-age invariably describes those young loves which thrill us most splendidly, hurt us most deeply, and remain in our memories when everything else is forgotten.

Eventually we decided to tell Roland’s mother that we were engaged ‘for three years or the duration of the War’, but to say nothing to my family until Roland’s leave was over. Exhausted and excited as I was, I felt unable to face either conventional congratulations or the raising of equally conventional obstacles. My father, I was convinced, would want to spend precious moments in asking Roland how he proposed to ‘keep’ me - an inquiry which I thought both irrelevant and insulting. I was already determined that, whether married or not, I would support myself, preferably by writing, and never become a financial burden to my husband. I believed even then that personal freedom and dignity in marriage were incompatible with economic dependence; I also laboured under the happy delusion that literature was a profession in which self-support was rapidly attainable.

My parents, who not unnaturally expected some explanation for the series of journeys upon which Roland and I proposed to embark together, were obviously puzzled by our silence and by the casual brusquerie with which we treated both them and one another. When, a few days later, I did tell them that we considered ourselves engaged, they received the news with calmness if not with enthusiasm, and protested only about our failure to mention the fact. This dénouement, after all, was hardly unexpected, and the War - as my mother by much unobtrusive co-operation had tried to make clear to me - had already begun to create a change of heart in parents brought up in the Victorian belief that the financial aspect of marriage mattered more than any other. The War has little enough to its credit, but it did break the tradition that venereal disease or sexual brutality in a husband was amply compensated by an elegant bank-balance.

Throughout our few hours in Buxton and again on the way back to London, Roland and I remained cold and rather formal with one another. We did discuss, very earnestly, the relation between love’s spiritual elements and its physical basis, but in 1915 such a conversation was calculated to increase perversity and embarrassment rather than to remove them, and we almost welcomed the interruption provided by a luncheon that we had arranged with Edward and Victor at the St Pancras Hotel.

Dressed in their newest and cleanest uniforms, with sprucely brushed hair and well-polished boots, Victor and Edward, who was still marking time in the southern counties waiting for his final orders, resembled an exceptionally tall Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Roland, with his shabby tunic and worn Sam Browne belt, looked a war-scarred warrior beside them, and over a prolonged meal the two bombarded him with eager, excited questions, which he answered with the calm nonchalance of a professional instructor.

Victor, now almost recovered from the after-effects of his cerebro-spinal meningitis, told us that he, like Roland, had recently been gazetted first lieutenant.

‘In my case, though,’ he observed appreciatively, ‘it was merely for gallant conduct in the hospital.’

Both he and Edward took our engagement entirely for granted - a fact which made their congratulations more tolerable than we had expected. Edward even appeared disappointed that we had not caused a little excitement by a secret and hasty marriage.

‘After all,’ he remarked, ‘you’re only giving a name to what has existed for quite a long time.’

11

As the train drew slowly into Lowestoft that evening, my nervousness at the prospect of meeting Roland’s family was intensified by the grim strangeness of the shrouded east coast. In the vanishing light the sea was visible only as a vast grey shadow, scarcely distinguishable from smaller shadows of floating cloud in a gently wind-blown sky. Far out to sea, the tiny twinkling eyes of buoys and vessels starred the vague dimness. As we drove through the streets, the faint outlines of the buildings and the muffled stillness broken only by the smooth wash of the waves on the shore, gave the curious impression of a town wrapped in fog. Until his parents’ house appeared, a warm refuge from the colourless twilight, all that I could see reminded me of the dreamy, intangible world of Pierre Loti’s Pêcheur D’Islande.

Tall and round and turret-like, the house, Heather Cliff, had been built with an immense number of seaward-looking windows. As it stood alone near a machine-gun station at the extreme end of the town, it provided a conspicuous landmark for ships far out to sea; consequently no lights were permitted except in the few back rooms, and the whole family lived in a state of semi-preparation for departure in case Zeppelin raids and possible bombardments should prove too disturbing to literary production.

It was somewhat disconcerting to be shown into a pitch-dark house and instantly surrounded by vague, alarming figures - the vital mother, the unknown father, and, perhaps most intimidating of all, the two adolescents, Roland’s seventeen-year-old sister and his fourteen-year-old naval cadet brother. These two, I felt sure, would display either exaggerated tact or youthful imperviousness to ‘atmosphere’. Actually, they exhibited both in turn.

Roland’s mother received me with warmth and generosity, though she was somewhat perturbed by our flippant announcement that we were engaged ‘for three years or the duration of the War’. Love, for her, was something to be gloried in and acknowledged; like so many others, she had not seen enough of the War at first hand to realise how quickly romance was being replaced by bitterness and pessimism in all the young lovers whom 1914 had caught at the end of their teens. But though our sense of love’s glamour seemed to her inadequate, I am still glad to remember the eager sympathy with which she so bravely helped me through months of suspense that without her unhesitating acceptance of me would have been unendurable.

In Roland’s bedroom, where at last we were allowed a light, she took both my hands and kissed me impulsively.

‘Why!’ she exclaimed, ‘what a tiny thing you are! I didn’t realise you were so little. I feel as if I wanted to pick you up and carry you about!’

Roland told me that she said to him afterwards: ‘Traditionally, I suppose, I ought to hate her - but I don’t.’

His father,

whose vigorous red hair and individualistic moustache gave him the appearance of a benevolent Swinburne, extended to me an equally kind though less definite welcome; and later I was to listen with rapt fascination to his tales of literary London and the adventurous journalistic world.

This general glowing warmth of acceptance banished in a few moments my suppressed fear of the household, though after the colourless formality of Buxton society I found somewhat embarrassing the family’s habit of frankly discussing personal appearances in front of their owners. But I drank in thirstily the literary gossip which I had never heard before - except in very small snatches from Roland, who, unlike the rest of his family, was not much addicted to this agreeable form of entertainment - and listened spell-bound to his mother’s stories ‘of her and publishers and their annoying habits’. The whole atmosphere of the house thrilled and delighted me, and made me more than ever conscious of Buxton limitations and my young lady’s upbringing.

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925