- Home

- Vera Brittain

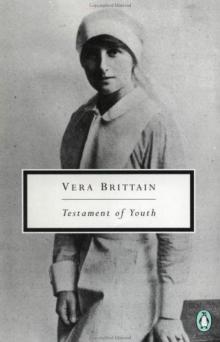

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Page 2

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Read online

Page 2

In none of these works, however, did Brittain find adequate acknowledgment of the role of women in the war; indeed, she attacked Aldington’s novel for its misogyny and for the way in which it poured a ‘cynical fury of scorn’ on the wartime suffering of women. It was obvious to her that no man, however sympathetic, would be able to speak for women.

The war was a phase of life in which women’s experience did differ vastly from men’s and I make no puerile claim to equality of suffering and service when I maintain that any picture of the war years is incomplete which omits those aspects that mainly concerned women . . . The woman is still silent who, by presenting the war in its true perspective in her own life, will illuminate its meaning afresh for its own generation.25

By the time she wrote those words, at the beginning of 1931, she had already embarked on her own book, and clearly intended to be that woman.

Of course, Testament of Youth was very far from being the only account by a woman of her wartime experience, though it remains the best known.26 A large number had been published both during the war and in the years since, and for some of these, like Mary Lee’s 1929 novel, It’s a Great War, written from an American standpoint, Brittain had expressed warm words of commendation. She would also later read, ‘with deep interest and sympathy’, Irene Rathbone’s novel, We That Were Young (1932), based on Rathbone’s own experiences as a VAD, like Brittain, at the 1st London General Hospital in Camberwell. It conveyed, as no other book had done to date, the full horror of nursing the mutilated and wounded.27 In the later stages of writing Testament of Youth in the summer of 1932, Brittain was concerned that Ruth Holland’s recently published novel, The Lost Generation, anticipated her own theme. Overall it is difficult to avoid the impression that Brittain wanted to perpetuate the idea that hers was the one work about the war by a woman that mattered. 28 On the other hand, none of these other books are of comparable stature to Testament of Youth, lacking its range and narrative power. As Winifred Holtby wrote on one occasion when Brittain needed particular reassurance, ‘Personally, I’m not in the least afraid of other people’s books being like yours. What other woman writing has both your experience and your political training?’29

However, it is the men in Vera Brittain’s story who typify the central founding myth on which Testament of Youth is based. Although in the early stages of the book’s evolution she claimed to be writing for her generation of women, she was subsequently to expand her claim to include her generation of both sexes.30 Certainly, nothing else in the literature of the First World War charts so clearly the path leading from the erosion of innocence, with the destruction of the public schoolboys’ heroic illusions, to the survivors’ final disillusionment that the sacrifice of the dead had been in vain. Testament of Youth is the locus classicus of the myth of the lost generation, and it is important to understand why this should be so. Brittain’s male friends were representative of the subalterns who went straight from their public schools or Oxbridge, in the early period of the war, to the killing fields of Flanders and France. As a demographic class these junior officers show mortality rates significantly higher than those of other officers or of the army as a whole. Uppingham School, where three of Brittain’s circle were educated, lost about one in five of every old boy that served. The Bishop of Malvern, dedicating the war memorial at another public school, Malvern College, said that the loss of former pupils in the war ‘can only be described as the wiping out of a generation’.31 The existence of a lost generation is not literally true, and is entirely unsupported by the statistical evidence; 32 but, given the disproportionate death rate among junior officers, it is perhaps no wonder that Brittain believed that ‘the finest flowers of English manhood had been plucked from a whole generation’. Robert Wohl has shown how this cult of a missing generation provided ‘an important self-image for the survivors from within the educated elite and a psychologically satisfying and perhaps even necessary explanation of what happened to them after the war’.33

Vera Brittain had another aim in writing her book: to warn the next generation of the danger of succumbing out of naïve idealism to the false glamour of war. This gives Testament of Youth a significant difference of tone that sets it apart from the work of the war’s male memoirists. Whereas a writer like Edmund Blunden tries to evoke the senselessness and confusion of trench warfare by revealing the depth of the war’s ironic cruelty, Brittain, contrastingly, tries to provide a reasoned exposition of why the war had occurred and how war in the future might be averted. The publication of Testament of Youth at the end of August 1933 exactly matched the mood of international foreboding. It was the year in which Hitler had become chancellor of Germany, the Japanese had renewed their attack on Manchuria, and there had been difficulties over negotiations for disarmament at the League of Nations in Geneva. As a result, parallels between the tense world situation and the weeks leading up to the outbreak of war in 1914 were endemic in the press. Yet while Brittain often referred to Testament of Youth as her ‘vehement protest against war’, she was, at the time of writing it, still several years away from declaring herself a pacifist. In 1933, as the final chapters of her autobiography show, she clung to the fading promise of an internationalist solution as represented by the League of Nations. However, the process of writing her book undoubtedly hastened her transition to pacifism in 1937, for looking back at the tumultuous events of her youth, she could for the first time separate her respect for the heroism and endurance of her male friends from the issue of what they had actually been fighting for.

Testament of Youth has been so often adduced as an historical source in studies of the First World War that it might be easy to forget that it is not history but autobiography and, moreover, autobiography that at a number of points uses novelistic devices of suspense and romance to heighten reality. This is particularly true of Brittain’s treatment of her relationship with Roland Leighton, where rather than dealing with the complex web of emotions that existed on both sides she creates a conventional love story. She had carefully researched the background to the war in historical records, like the Annual Register and in the collections of the British Red Cross Society and the Imperial War Museum, and also employed a patchwork of letters and diaries to bring the characters of her major protagonists alive, which provide the backbone of the finished book. But she was fearful of ‘numerous inaccuracies through queer tricks of memory’,34 and inevitably some mistakes slipped through the net. Her narrative of the period she had spent as a VAD at the 24 General at Etaples, from August 1917 to April 1918, does not possess the reliability of precise chronology and detail of earlier parts of Testament of Youth. She had ceased to keep a diary after returning from Malta in May 1917, and had only some letters to her mother, a few rushed notes to Edward, and a sometimes hazy recollection of events some fifteen years or so after they had taken place. For her - highly inaccurate - description of the Etaples mutiny, which had occurred in September 1917 while she was at the camp, she had been forced to rely on little more than the memory of Harry Pearson, an ex-soldier and friend of Winifred Holtby, who had had no direct involvement in the events either.35

The publication of Vera Brittain’s wartime diaries and correspondence has revealed the extent of the complexity and ambivalence underlying her contemporary responses to the war. The evidence of these private records demonstrates that while at times she could rail against the war with anger and distress, at others she took refuge in a consolatory rhetoric rooted in traditional values of patriotism, sacrifice and idealism of the kind espoused by the wartime propaganda of both Church and State, or the sonnets of Rupert Brooke. In her letters written after Roland’s death, for instance, her need to continue believing that the war was being fought for some worthwhile end - manifest in such gung-ho sentiments as, ‘It is a great thing to live in these tremendous times’,36 or her conviction that war is an immense purgation37 - is perhaps entirely understandable. But equally, in Testament of Youth, it is not surprising to find that this kin

d of ambivalence is largely absent, and that Brittain is reluctant to confront her own susceptibility as a younger woman to the glamour of war, and unwilling to probe too deeply the roots of her own idealism in 1914.38 For by the time she had completed her autobiography, Vera Brittain was ready to reject anything that identified war ‘with grey crosses, and supreme sacrifices, and red poppies blowing against a serene blue sky’.39

In 1989, while writing Vera Brittain’s biography, I travelled to the Somme to pay a visit to Roland Leighton’s grave at Louvencourt. Our party of four, including two of Vera Brittain’s grandchildren, spent the night in Albert, at the Hotel de la Paix, where Brittain herself had lunched in July 1933 during the second of her two visits to the cemetery where Roland was buried; and the next morning, which happened to be Remembrance Sunday, we made the hilly drive to Louvencourt. On the south-east side of the village, a large stone cross dominates the skyline, surrounded by acres of tranquil farmland. It is a small cemetery, of 151 Commonwealth and 76 French graves, beautifully cared for, as are all the military cemeteries of the First World War, by the Commonwealth Graves Commission. Roland’s grave is in the middle, not far from the memorial cross and cenotaph, and its inscription includes the closing line from W.E. Henley’s ‘Echoes: XLII’, ‘Never Goodbye’.

I found the visitors’ book in a little cupboard in the wall. Among its messages, I counted no fewer than ten people from around the world who, in the period of just two months, had come to this relatively out of the way area of the Somme in order to pay tribute to Roland Leighton - and to pay tribute to him because they had read about his brief life and early death in Testament of Youth. As Shirley Williams, Vera Brittain’s daughter, says in her preface, it is a precious sort of immortality.

More than seventy years after its first publication, Testament of Youth’s power to disturb and to move remains undiminished.40 Vera Brittain’s ‘passionate plea for peace’, which attempts to show ‘without any polite disguise, the agony of war to the individual and its destructiveness to the human race’,41 is one that, tragically, still resonates in our world today.

Mark Bostridge London, February 2004

Preface

It is now sixty years since the First World War ended, and few are still alive who survived that fearful experience at first hand. The War should now be a part of history; the weapons, the uniforms, the static horror of battles fought in trenches are all obsolete now. Yet the First World War refuses to fade away. It has marked all of us who were in any way associated with it, even at one generation’s remove through our parents. The books, the poetry, the artefacts of those four and a half years still speak to young men and women who were not even born when the Second World War ended.

Why are we so haunted? I think it is because of the terrible irony of the War; the idealism and high-mindedness that led boys and men in their hundreds of thousands to volunteer to fight and, often, to die; the obscenity of the square miles of mud, barbed wire, broken trees and shattered bodies into which they were flung, battalion after battalion; and the total imbalance between the causes for which the war was fought on both sides, as against the scale of the human sacrifice. As Wilfred Owen put it in ‘The Send-Off ’,

Shall they return to beatings of great bells

In wild train-loads?

A few, a few, too few for drums and yells

There is another reason, too. The First World War was the culmination of personal war; men saw the other human being they had killed, visibly dead. Men fought with bayonets, with knives or even their bare hands. The guns themselves were on the battlefields, thick with smoke, the gunners sweaty and mudbound. War had not yet become a pitting of scientist against scientist or technologist against technologist. Death was not, on either side, elimination through pressing a button, but something seen and experienced personally, bloody, pathetic and foul.

My own picture of the War was gleaned from my mother. Her life, like that of so many of her contemporaries who were actually in the fighting or dealing with its consequences, was shaped by it and shadowed by it. It was hard for her to laugh unconstrainedly; at the back of her mind, the row upon row of wooden crosses were planted too deeply. Through her, I learned how much courage it took to live on in service to the world when all those one loved best were gone: her fiancé first, her best friend, her beloved only brother. The only salvation was work, particularly the work of patching and repairing those who were still alive. After the War, the work went on - writing, campaigning, organising against war. My mother became a lifelong pacifist. I still remember her in her seventies, determinedly sitting in a CND demonstration, and being gently removed by the police.

Testament of Youth is, I think, the undisputed classic book about the First World War written by a woman, and indeed a woman whose childhood had been a very sheltered one. It is an autobiography and also an elegy for a generation. For many men and women, it described movingly how they themselves felt. Time and again, in small Welsh towns and in big Northern cities, someone has come up to me after a meeting to ask if my mother was indeed the author of Testament of Youth, and to say how much it meant to them. It is a precious sort of immortality.

I hope now that a new generation, more distant from the First World War, will discover the anguish and pain in the lives of those young people sixty years ago; and in discovering will understand.

Shirley Williams August 1977

Author’s Acknowledgments

My very warm and grateful thanks are due to Roland Leighton’s family for their generosity in allowing me to publish his poems and quote from his letters; to my parents for permitting me to reproduce E. H. B.’s letters and his song ‘L’Envoi,’ as well as for their untiring assistance in the tracing of war letters and documents; to B. B. for the extracts from my uncle’s letters which appear in Chapter VII; to my husband for the letters quoted in Chapter XII and for much valuable criticism; and to Winifred Holtby, whose unstinted services no words can adequately acknowledge or describe, for the use of her letters and the poem ‘Trains in France,’ for her help in correcting the proofs, and for the unfailing co-operation of her constant advice and her vivid memory. I am, in addition, greatly indebted to Madame Smeterlin for correcting proof of the song ‘L’Envoi’; to Mr H. H. Price, of Trinity College, Oxford, for verifying the quotation from Cicero at the beginning of Part III; and to the officials of the Imperial War Museum for their courtesy and kindness on several occasions. I should also like to thank Miss Phyllis Bentley very gratefully indeed for much generous help and encouragement during the final year of this book’s vicissitudes.

Acknowledgments and thanks are due to the following for kindly permitting the use of copyright poems or long quotations: Miss May Wedderburn Cannan, for ‘When The Vision Dies’; Mr Rudyard Kipling for the quotation from ‘Dirge of Dead Sisters’ out of The Five Nations (copyright 1903 by Rudyard Kipling and reprinted by permission from Messrs A. P. Watt & Son, agents, Messrs Methuen & Co., Ltd., London, the Macmillan Company, Toronto, and Messrs Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., New York, Publishers); Miss Rose Macaulay, for ‘Picnic, July, 1917’; Mr Walter de la Mare for ‘The Ghost,’ out of The Listeners; Mr Wilfred Meynell for ‘Renouncement,’ by Alice Meynell; Sir Owen Seaman for ‘“The Soul of a Nation”’; Mr Basil Blackwell for the poems from Oxford Poetry, 1920 and quotations from two numbers of the Oxford Outlook; Messrs Macmillan & Co., Ltd., London, and Messrs Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, for quotations from the poems of W. E. Henley; Messrs John Murray, for ‘The Death of Youth,’ from Verse and Prose in Peace and War, by William Noel Hodgson; the literary executor, Messrs Sidgwick & Jackson, Ltd., and Messrs Dodd, Mead & Co., New York (copyright, 1915, by Dodd, Mead & Company, Inc.), for the sonnet (‘Suggested by Some of the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research’) by Rupert Brooke. I also want to express my gratitude to the authors of the poems quoted on p. 122 (from London Opinion) and p. 155 (from the Westminster Gazette), as well as my regret that I was unable to approach them person

ally, because in the one case the poem was signed only by initials and in the other the long-ago date of publication was unknown.

Finally, I am much indebted to the editors of The Times, the Observer, Time and Tide, the Daily Mail, the Star, and the Oxford Chronicle for the valuable assistance of their columns in the reconstruction of recent history.

V. B. May, 1933

Foreword

For nearly a decade I have wanted, with a growing sense of urgency, to write something which would show what the whole War and post-war period - roughly, from the years leading up to 1914 until about 1925 - has meant to the men and women of my generation, the generation of those boys and girls who grew up just before the War broke out. I wanted to give too, if I could, an impression of the changes which that period brought about in the minds and lives of very different groups of individuals belonging to the large section of middle-class society from which my own family comes.

Only, I felt, by some such attempt to write history in terms of personal life could I rescue something that might be of value, some element of truth and hope and usefulness, from the smashing up of my own youth by the War. It is true that to do it meant looking back into a past of which many of us, preferring to contemplate to-morrow rather than yesterday, believe ourselves to be tired. But it is only in the light of that past that we, the depleted generation now coming into the control of public affairs, the generation which has to make the present and endeavour to mould the future, can understand ourselves or hope to be understood by our successors. I knew that until I had tried to contribute to this understanding, I could never write anything in the least worth while.

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925