- Home

- Vera Brittain

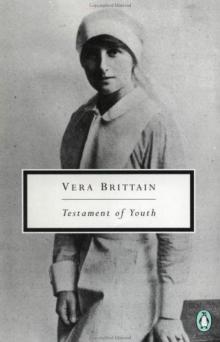

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Page 13

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Read online

Page 13

‘I like it very well indeed,’ I informed him, ‘but I am never likely to fall into the typical college woman’s blind infatuation with everybody and everything, or to think this place the only place, or these ideas the only ideas. It is an immense advantage to have been at home for a while and have seen other points of view besides this one. At present I am almost equally aware of its limitations and its advantages. It is a delightful change to me to be in surroundings where work is expected of you, instead of where you are thought a fool for wanting to do it, and of course the whole atmosphere of Oxford is ideal if you want to study or think or prepare to be. The last “if ” however points to one of the limitations here, as already I have come across several people who seem to regard their residence here as an end in itself, instead of a mere preparation for better and wider things in the future.’

In the intervals snatched from cocoa, Greek and religion, I saw something of Edward. On account of the strict chaperonage regulations of those days (always disrespectfully referred to as ‘chap. rules’) I was not allowed to go to his rooms in Oriel Street lest I should encounter the seductive gaze of some other undergraduate, but I met him in cafés and at the practices of the Bach Choir and Orchestra, for which Dr Allen had chosen him to be a first violin. If ever he dropped in unexpectedly to tea with me at Somerville, I was obliged hastily to eject any friends who might be sitting in my room, for fear his tabooed sex might contaminate their girlish integrity.

Towards the end of November he was gazetted to the 11th Sherwood Foresters, and the next day he left Oxford for Sandgate. With his tall figure, his long beautiful hands, and the dark arched eyebrows which almost met above his half-sad, half-amused eyes, he looked so handsome in his new second-lieutenant’s uniform that the fear which I had felt when he returned from Aldershot on the eve of the War suddenly clutched me again. Reluctantly I said good-bye to him in the Woodstock Road at the entrance to Little Clarendon Street, almost opposite the place where the Oxford War Memorial was to be erected ten years afterwards ‘In memory of those who fought and those who fell’.

I often thought of him in camp as the November rain deluged the city and churned the Oxfordshire roads into mud, and once again the War crept forward a little from its retreat in the back of my mind. One student in my Year had a brother who was actually at the front; I contemplated her with awe and discomfort, and carefully avoided her for the rest of the term.

5

The second week in December brought Responsions Greek, which I passed easily enough. The fact that this was done on six weeks’ study of that lovely language, which is totally unsuited to such disrespectful treatment, testifies to the simplicity of Responsions as an examination, and to the unnecessary circumambulation of the alternative with which I had burdened myself. I returned home to find Buxton almost a military centre, with the enormous Empire Hotel just below our gates turned into a depot for Territorials.

At first I tried to communicate my enthusiasm for Oxford to the family circle, for Edward’s absence had left a depressing blank in the household, and after the congenial companionships of Oxford I felt lonely and almost a stranger. I did not, however, find my parents susceptible to infection. My father had an idée fixe about university dons, all of whom he believed to be ‘dried up’ and ‘coldblooded’, while my long-suffering mother, who must have endured indescribable ennui during the months in which I was immersed in examinations, could only reiterate her thankfulness that I had done Responsions away from Buxton, as she ‘would have got so bored hearing about it always’.

After describing this lamentable failure to impress my family, my diary records that on December 15th, 1914, I went with my mother for a day’s shopping in Manchester. While I was there, I saw on placards carried by vociferous paper-boys the news of that morning’s raid by German ships on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, but no telepathic vision had shown me through the early mists of that winter’s day the individual with whom my future was to be so closely bound, marching with her fellow-schoolgirls from Queen Margaret’s, Scarborough, beneath the falling shells. In her second novel, The Crowded Street, she has given a dramatic account of the bombardment, but five dark and adventurous years were to pass before I met Winifred Holtby. That afternoon the news of the raid impressed me less than my purchase of a little black moiré and velvet hat trimmed with red roses. It was one of the prettiest hats that I have ever had, and also one of the most memorable, for I was to be indescribably happy while wearing it, yet in the end to tear off the roses in a gesture of impotent despair.

That first wartime Christmas seemed a strange and chilling experience to us who had always been accustomed to the exuberant house-decorating and present-giving of the prosperous pre-war years.

‘A good many people,’ I observed, ‘have decided that they are both too poor and too miserable to remember their friends, particularly the rich people who have no one at all in any danger. The poorer ones, and those who are in anxiety about something or other, have all made an effort to do the same as usual. At St John’s . . . we had the inevitable sermon dwelling on the obvious incongruity of celebrating the birth of the Prince of Peace while the world was at war.’

Edward, who had succeeded in getting Christmas leave, was with us in Buxton. It was the last Christmas that we spent together as a family, and the unspoken but haunting consciousness in all our minds that perhaps it might be, somewhat subdued the pride with which we displayed him to acquaintances in the Pavilion Gardens. He endeavoured to cheer us up by telling us that the British and French armies could drive the Germans back whenever they chose and would have done so weeks ago had they not preferred to wait for the New Armies to come out in the spring and turn the action into a decisive victory. Better authenticated than this optimistic information was the news that Roland - who had sent me his photograph in exchange for one of mine, together with five books, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Pêcheur D’Islande, The Seven Seas, Maeterlinck’s Monna Vanna and Turgenev’s On the Eve - was spending Christmas in London at a flat temporarily taken by his mother near Regent’s Park.

It had already been arranged that at the end of the year I was to stay for two or three days in my maternal grandmother’s small house at Purley, and be taken into town by an aunt to buy clothes and college furniture. The coincidence seemed to have been specially designed by a benevolent destiny. When I thanked Roland for the books, I told him that I was coming up to town, and by return of post he had planned a series of meetings.

6

Incredible as it may seem to modern youth, it was then considered correct and inevitable that my aunt should cling to me like a limpet throughout the precious hours that I spent with Roland. But she was benevolent and enormously interested in our mutual attraction, and after we had all lunched and shopped together, she and Edward, who was going back to his battalion, tactfully walked towards Charing Cross while Roland and I loitered down Regent Street.

I longed to look at him closely and yet was too shy: his uniform and little moustache had changed him from a boy into a man, and one so large and powerful that even in the splendour of the rose-trimmed hat and a new squirrel coat given me by my father, I felt like a midget beside him. Months of intimate correspondence had bound us together, and yet between us was this physical barrier of the too conscious, too sensitive flesh. It was getting dark and all the streets were dim, for the first German air raid had occurred just before Christmas, and the period of Darkest London had begun. In the sky the searchlight, a faint, detached glimmer, quivered at the edges of the clouds, or slowly crawled, a luminous pencil, across the deep indigo spaces between. Roland, who had worked one himself, was immensely amused at my naïve absorption, and for the first time tentatively took my arm to guide me across the darkening streets. In those days people’s emotions, for all the War’s challenge, still marched deliberately and circumspectly to their logical conclusion.

As I undressed some hours later in the tiny bedroom of my grandmother’s house, I no longer wonder

ed what I really thought of him. Glowing with a warmth that defied the bitter cold of the fireless hearth, I hardly waited to throw my woollen dressing-gown over my nightdress before seizing the familiar black book and my friendly fountain pen.

‘O Roland,’ I wrote, in the religious ecstasy of young love sharpened by the War to a poignancy beyond expression, ‘Brilliant, reserved, extravagant personality - I wonder if I shall have found you only to lose you again, or if Time will spare us till it may come about that the greatest word in the world - of which now I can only think and dare not name - shall be used between us. God knows, and will answer.’

In spite of the War, the next day was heaven.

At the Florence Restaurant, still aunt-chaperoned, I lunched with Roland and was quite unable - and indeed did not try very hard - to shake him off at my dressmaker’s or my milliner’s, or even in the underclothing department at D. H. Evans. I hardly knew what I was buying; the garments and the furniture which had interested me so intensely had somehow lost their fascination, and I chose Leonardo da Vinci prints for my room with my judgment blinded by the dazzling but disturbing fact that in half an hour’s time I was to meet Roland’s mother and sister at the Criterion for tea.

In the end we were late, and drove there in a taxi. Roland’s mother was waiting for us in the lounge. Picturesquely dressed in rich furs and velvets, she appeared to my rapturous eyes as the individual embodiment of that distant Eldorado, the world of letters. I knew that I was in for a critical inspection, for to Roland, who had told her ‘all about me’, including the fact that I was at Somerville, she had said: ‘Why does she want to go to Oxford? It’s no use to a writer - except of treatises.’ I was, therefore, pleased and relieved when she turned to him and remarked: ‘Why, she’s quite human, after all! I thought she might be very academic and learned.’

The mutual devotion between herself and Roland was very pleasant to see. It was her pride and delight that she understood him as few mothers understand sons or daughters, and their instinctive knowledge of each other’s moods was certainly remarkable. A little apart from that magic circle of intimacy sat the fifth member of the party, Roland’s sister Clare, who was then a jolly, vivacious girl of sixteen, with two long thick plaits and a disarming naïvete of manner which made her seem very young for her age. If any disconcerting prophet had whispered to Roland and me how successful she was destined to become, we should then have treated him, I think, with amused incredulity.

I remember little more of that Criterion tea, but it left me with the agreeable impression that Roland’s mother, whose generous temperament predisposed her favourably towards youthful love-affairs, definitely approved of my friendship with Roland. She disliked, I gathered, the strident type of girl who boasted of being ‘modern’, and I was too much the pretty-pretty type ever to seem aggressively up to date. As one Army Sister remarked of me three years later to another with whom I had become close friends: ‘That V.A.D. of yours is a pretty little thing, but she’s got a vacant face - very vacant!’

7

At dinner that evening - once again at the Florence - Roland gave me a bunch of tall pink roses with a touch of orange in their colouring and the sweetest scent in the world. He watched me fasten them, in the fashion of the moment, just above my waist against the dark blue silk of my dress, and murmured ‘Yes!’ under his breath. In the warm atmosphere of the restaurant, their wistful, tender perfume clung about us like a benediction.

Incongruously we talked, that dinner-time, about the way we should like to be buried. I thought I should prefer to be burnt on a pyre, like Achilles, but Roland wanted to be put Viking-wise in a flaming boat, and left to drift out to sea. I asked him quite suddenly: ‘If you could choose your death, would you like to be killed in action?’ My aunt was horrified at this inconsiderate directness. ‘My dear girl, why do you talk about such things?’ she exclaimed, but Roland replied quite quietly: ‘Yes, I should. I don’t want to die, but if I must I should like to die that way. Anyhow I should hate to go all through this War without being wounded at all; I should want something to prove that I had been in action.’

Long afterwards, Victor told me that Roland had once remarked, with the dramatic emphasis inherited from his family, that he could wish for no better end than to be found dead in a trench at dawn.

After dinner he took us to His Majesty’s Theatre to see Sir Herbert Tree’s production of David Copperfield. No doubt this performance was most spectacular, but though I apparently witnessed the whole of it, I was hardly conscious even of the changes of scene. In one interval, I whispered to Roland how much I had liked his mother.

‘She thought you the most charming girl she had ever met!’ he told me enthusiastically.

‘Oh, I’m so relieved!’ I exclaimed. ‘You don’t know what I should have felt like if she’d disliked me!’

‘I knew she wouldn’t,’ he observed reassuringly. ‘I knew just what she would think - her tastes are very much the same as mine . . .’

‘Sh-h—!’ reprimanded our unsympathetic neighbours as the curtain went up.

At Charing Cross, with half an hour to wait for the last train to Purley, we walked together up and down the platform. It was New Year’s Eve, a bright night with infinities of stars and a cold, brilliant moon; the station was crowded with soldiers and their friends who had gathered there to greet the New Year. What would it bring, that menacing 1915?

Neither Roland nor I was able to continue the ardent conversation that had been so easy in the theatre. After two unforgettable days which seemed to relegate the whole of our previous experience into a dim and entirely insignificant past, we had to leave one another just as everything was beginning, and we did not know - as in those days no one for whom France loomed in the distance ever could know - when or even whether we should meet again. Just before the train was due to leave I got into the carriage, but it did not actually go for another ten minutes, and we gazed at one another submerged in complete, melancholy silence.

My aunt, intending, I suppose, to relieve the strain - which must certainly have made the atmosphere uncomfortable for a third party - asked us jokingly: ‘Why don’t you say something? Is it too deep for words?’

We laughed rather constrainedly and said that we hoped it wasn’t as bad as all that, but in our hearts we knew that it was just as bad and a great deal worse. The previous night I had become ecstatically conscious that I loved him; on that New Year’s Eve I realised that he, too, loved me, and the knowledge that had been an unutterable joy so long as any part of the evening remained became an anguish that no words could describe as soon as we had to say good-bye.

The New Year came in as I sat in the train, trying to picture the dark, uncertain future, and watching the dim railway lights in a blurred mist go swiftly by. When at last I was alone in my bedroom, the tears that had blurred the lights fell unrestrainedly upon the black book to which I had confided so much repressed bitterness, so many private aspirations. It was now to receive a secret of a more primitive kind, for I wrote in it that I would gladly give all that I had lived and hoped for during my few years of conscious ambition, not, for the first time, to astonish the world by some brilliant achievement, but one day to call a child of Roland’s my own.

8

After all, I saw him again quite soon.

But first there came a letter telling me that he too had witnessed, not without emotion, the coming of 1915.

‘When I left you I stood by the fountain in Piccadilly Circus to see the New Year in. It was a glorious night, with a full moon so brightly white as to seem blue slung like an arc-lamp directly overhead. I had that feeling of extreme loneliness one is so often conscious of in a large crowd. There was very little demonstration; two Frenchmen standing up in a cab singing the “Marseillaise”; a few women and some soldiers behind me holding hands and softly humming “Auld Lang Syne”. When twelve o’clock struck there was only a little shudder among the crowd and a distant muffled cheer and then everyone seemed

to melt away again, leaving me standing there with tears in my eyes and feeling absolutely wretched.’

The letter ended with half a dozen little words which, for all their gentle restraint, once more transformed speculation into bright, sorrowful certainty.

‘You are a dear, you know.’

The next day, in church, Cowper’s hymn, ‘God moves in a mysterious way’, so often sung during the War by a nation growing ever more desperately anxious to be reassured and consoled, almost started me weeping; as I listened with swimming eyes to its gentle, melodious verses, I wondered whether I should ever have sufficient understanding of the world’s ironic pattern to be able to accept the comfort that they offered:

Ye fearful saints, fresh courage take;

The clouds ye so much dread

Are big with mercy, and shall break

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925

Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925